Rediscovering Armenia Guidebook- Yerevan

| Rediscovering Armenia Guidebook |

|---|

| Intro

Armenia - Yerevan, Aragatsotn, Ararat, Armavir, Gegharkunik, Kotayk, Lori, Shirak, Syunik, Tavush, Vayots Dzor Artsakh (Karabakh) - (Stepanakert, Askeran, Hadrut, Martakert, Martuni, Shushi, Shahumyan, Kashatagh) Worldwide - Nakhichevan, Western Armenia, Cilicia, Georgia, Jerusalem, Maps, Index |

EXPLORING YEREVAN

The land of today's Armenia was for most of its history a rural society, with few cities of its own. The modern city of Yerevan was built on tragedy and dreams. Little more than a garrison town of mud-brick and gardens before its first brief experience as capital of an independent Armenia in 1918, the city burgeoned under Soviet rule. The flood of refugees from the 1915 holocaust and its aftermath fueled an uneasy but productive alliance between Armenian nationalism and Soviet hopes of spreading the Communist gospel through the Armenian Diaspora. Modern Yerevan was built, deliberately, to be the universal center and pole of attraction for the Diaspora, with an educational and cultural infrastructure far out of proportion to the size or intrinsic wealth of Soviet Armenia. Only now, with independence has Yerevan truly become the center of both the Republic of Armenia and the far-flung Armenian Diaspora.

In 1988, when the collapse of the Soviet Union became visible, Yerevan was a full-fledged, booming Soviet city of over 1 million people. A gracious street plan of parks, ring-roads, and tree-lined avenues had been laid out by the architect Alexander Tamanyan and his successors in the 1920s and 1930s for a population they dreamed might reach 200,000. That goal long surpassed, the process of expansion to reach the magic million-person threshold that qualified Yerevan for a metro and the other perquisites of a city of all-Union importance involved Armenia's successive First Secretaries in sordid expedients and half-finished, earthquake-vulnerable construction projects in sprawled, depressing suburbs. In the early 2000s, Yerevan experienced a huge building boom, and Alexander Tamanyan's plans for a pedestrian blvd. stretching from the Opera to Republic Square were realized. Large building also sprung up along the park between Arami and Buzand streets, and in other points around the city. Many of Yerevan's oldest and finest little buildings have been demolished in order to accommodate these projects, with an ever-shrinking number of pre-Soviet buildings remaining in Yerevan.

The success of the 1988 independence movement dealt the city a series of major shocks, first with the forced emigration of a centuries-old Muslim (mostly Azerbaijani Turkish) population, and its replacement by newly impoverished refugees from Baku. The disastrous collapse of the Soviet economic system (Armenia made high-tech pieces of everything, but produced all of practically nothing) triggered the economic migration of hundreds of thousands of impoverished Armenians bound for the bright lights of Moscow or Glendale. A reliable census took place in 2001, counting just over 3 million heads in the country, down from an estimated 3.8 million a dozen years earlier.

1. Archaeology

Yerevan is a very ancient place. Caves in the walls of the Hrazdan river gorge, particularly near the modern Yerevanian Lake, show traces of Stone Age habitation. The substantial Chalcolithic settlement of Shengavit, scientifically of great importance for the prehistory of the whole region, is perched on the slope on the far side of the lake (from the airport road, take the road SE across the dam, then turn left). There you will find the crumbling circular foundations of a number of rubble and mud-brick houses, once surrounded by a stone fortification wall and with an underground passage leading to the river. Four settlement phases have been identified, from the end of the 4th millennium B.C. to the beginning of the second millennium B.C.

The Urartian kingdom centered on Lake Van in Eastern Turkey gave Yerevan its first major impetus. The Urartians built the citadel of Erebuni ☆ on the hill of that name in SE Yerevan. A substantial museum at the base of the hill formerly known as Arin Berd houses many of the finds, including a few examples of Urartu's splendid metalwork. The citadel itself was founded by Argishti I, son of Menua, King of Urartu in the year 782 B.C., the first Urartian conquest on the E side of the Arax. We know this on the basis of a cuneiform inscription discovered built into the fortification wall by the gate, an inscription which reads roughly as follows: "By the greatness of the god Khaldi, Argishti son of Menua built this great fortress, named it Erebuni, to the power of Biainili and the terror of its enemies. Argishti says: the land was waste, I undertook here great works..." Armenian scientists argue that one can derive the name Yerevan from Erebuni by a series of simple phonological shifts, suggesting that modern Yerevan is the lineal descendant of this 8c B.C. citadel. In 1968 the city of Yerevan marked the founding of the citadel as Yerevan's 2750th birthday, a celebration which is now marked each year.

The site has been heavily restored, not always well, and those restorations badly need their own restoration, making it difficult to separate original Urartian walls from Achaemenid Persian remodeling. In any case, enough survives to convey that this was a large, complex center, with shrines, palatial rooms with elaborately frescoed walls, and major storage facilities. A number of smaller cuneiform inscriptions on basalt building stones attest to a "susi," apparently an Urartian temple.

About a century after Erebuni was built, in the first year of Urartian King Rusa II, the inhabitants of Erebuni seem to have relocated to a citadel they called Teishebai URU (City of the God Teisheba), the site now known as Karmir Blur ("Red Hill") ⟪40.15363, 44.4530⟫. This site overlooks the Hrazdan river from a bluff downstream from Shengavit (from the airport road, cross the dam, turn right on Artashesyan Ave., then right again on Shirak St. about 1 km down, and go to the end). The site takes its name from the huge pile of decomposed red mud-brick, some of which still sits atop the impressive stone foundations of the city wall.

Yerevan's history fades away after Karmir Blur in terms of things to look at, with the early Armenian kings and Roman and Persian conquerors preferring Artaxiasata to the S and Vagharshapat/Ejmiatsin to the NW. The horrific earthquake of 1679 completed the destruction done by passing Arab, Mongol, Persian, and Ottoman armies over the centuries. Still, bits and pieces remain for the patient explorer.

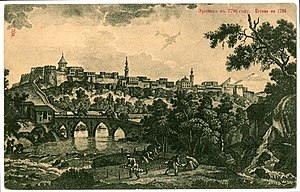

2. The Erivan Fortress

Reconstituted in the 17c as a Persian city-fortress guarding the marches with the Ottoman Empire, Yerevan was a key military/strategic point at the intersection of three empires. At the beginning of the 19c, first the French and later the British sent military experts to prop up Persia against Russian aggression. Drawing on their expertise, the last Khan of Yerevan made his headquarters the strongest and most modern fortress in the Persian Empire, with a cannon factory and arsenal. The palace was large and gracious, with fountains, a hall of mirrors, painted ceilings depicting the Persian epic hero Rostom, and other trappings of civilized living.

In 1804 Prince Tsitsianov led a Russian army against Yerevan, but was forced to withdraw, a number of Armenian notables and their retainers retreating with him to Georgia. Displeased with the lack of local Armenian assistance to his cause, the haughty Georgian prince penned a scornful letter in 1805 to the leading Armenian notables of Yerevan, Melik Abraham and Yüzbashi Gabriel, when they begged him to try again:

- "Unreliable Armenians with Persian souls -- You may for now eat our bread, hoping that you may purchase it. But if by next fall your people have not planted enough grain to have a surplus for sale, then be warned that by spring I shall chase you not only to Erevan but to Persia. Georgia is not required to feed parasites. As to your request to save the Armenians of Erevan, who are dying in the hands of unbelievers: do traitors deserve protection? Let them die like dogs; they deserve it. Last year when I surrounded the Erevan fortress, the Armenians of Erevan, who do not deserve even a grain of pity, were in control of Narin-Kale (note: an outlying bastion). They could have surrendered it to me but did not, and you, Yüzbashi, being the main advisor of Mohammad Khan of Erevan, were in league with them and helped the khan in his intrigues and lies against me. Now you have fled, and God has punished you for betraying the favors of his Imperial Majesty. Do you think I am like other generals, who do not realize that Armenians and Tatars are willing to sacrifice thousands for their own benefit? ... Do you, therefore, think that I can rely on the word of two yüzbashis and Persians, who promise to surrender the fortress upon the appearance of Russian forces? ..." (quoted in Bournoutian 1998)

Tsitsianov was murdered in 1806 outside the walls of Baku, and his loss was little lamented. Future Russian leaders were more diplomatic, and found the Armenians of Yerevan better allies, though by no means in a position to liberate themselves from the 3000 troops of the Persian garrison. General Gudovich tried and failed in 1808, but General Paskievich succeeded, entering Yerevan on October 2, 1827, as recounted in a British War Office summary:

- "As soon as Paskiewitch assumed the command-in chief (note: in 1827) he had a siege train carried up to the neighborhood of Erivan, which fortress was still held by the Persians. Leaving the train in a redoubt near Erivan, he marched to Abasabad, a new and regular European fortress on the banks of the Arax near Nachitschevan. This place opened its gates to him. Sardarabad, a large fortified village on a canal fed by the Arax, was next taken, and the stock of provisions found in it placed Paskiewitch in a position to commence the siege of Erivan. Erivan had already been twice unsuccessfully besieged, and was considered almost impregnable. The fortifications consisted of two walls, an outer 25 feet and an inner 35 feet high round three sides; the steep cliff of the ravine of the Zangi formed a natural defense on the fourth side. Two weak detached bastions on European principles had been added since an attack by General Gudevich. Trenches were advanced under the natural cover of the ground almost up to the foot of the walls. The batteries effected a breach in a single day's firing; many of the garrison deserted during the night, and on the following day Erivan was taken by assault."

Paskevich continued S to Tabriz, and forced Persia to cede all the territory N of the Arax river to the Russian Empire in the Treaty of Turkmenchay. Paskevich was rewarded with the title Count of Yerevan, and went on to further glory as the brutal suppressor of a revolt in Poland. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of Armenians flocked into the liberated territories from Persia and the Ottoman empire.

Yerevan itself remained a garrison town, but the fortress had lost its importance. When Berge visited Yerevan in January 1848, he reported that the thick, crenellated mud-brick walls of the Yerevan fortress were already deeply crevassed, dissolving in the rain as mud-brick does unless roofed and maintained. The Sardar's superficially splendid palace slowly melted as well, and had become an eyesore by mid-century. In Soviet times, the last traces of the fortress disappeared; the hulking basalt prison of the Yerevan Wine Factory marks the site, though the fortress walls once extended up and down the river as well as back toward town. An inscription in Armenian on the lower wall of the Wine Factory commemorates the staging in 1827 of a play by Griboyedov, a Russian diplomat/writer in Paskevich's entourage, who was murdered in 1829 with the rest of the Russian Embassy in Tehran.

3. The City

In 1827, Yerevan was a town of 1736 low mud-brick houses, 851 shops, 10 baths, seven caravansaries, and six public squares, set among gardens likewise walled with mud. Czar Nikolai I found no more endearing description for Yerevan during his one brief visit in 1837 than "a clay pot," and the Russian travel writer Mardovtsiev found little difference in the 1890s: "Clay houses with flat clay roofs, clay streets, clay squares, clay surroundings, in all directions clay and more clay." Yerevan remained a garrison town of 12,500 inhabitants, more than half Muslim, a place of low, flat-roofed houses and lush walled gardens, until the 20th century. Practically nothing of this earlier town remains, except in Kond, tucked between Saryan Street and the Dvin Hotel on Proshyan and Paronyan Streets. The hill of Kond was a predominantly Armenian neighborhood in Persian times, presided over by the Geghamyan family of meliks, Kond is the neighborhood that preserves a taste of the city's oriental past. There is a church and the remains of a mosque, which are covered in other sections, as well as the remains of an old bathhouse ⟪40.18077, 44.50244⟫. Set apart for preservation in Soviet times, Kond's winding alleyways and tumbledown houses have seen incongruous construction as well as talk from the government of tearing down and redeveloping the entire neighborhood. In the meantime, a careful search still reveals the crumbling archways and courtyards of an older Armenia.

The easiest access to Kond is by parking in front of the large Post office on Saryan St, and then walking uphill on the road to the left of the post office. Take a short right at the top of the road (behind the post office now) and then the first left up an alley of sorts. A quick left again on the next alley will wind you along a road of clay-walled houses and past an arch with a keystone dated 1863. Continuing around the houses, bearing left at each intersection, will bring you back to your starting point.

4. The Red Bridge

The multi-arched medieval Red Bridge of 1679 stand on the Hrazdan river just below the fortress, now the site of the Yerevan Wine Factory at the bottom of Mashtots Blvd. Rebuilt just after the great earthquake at the expense of the wealthy merchant Hoca P'ilavi, this bridge is commonly known as the Red Bridge from the tuff used. It was extensively modified in 1830 by the Russians. There had been a bridge at this site since very early times, the only connection between the city-fortress of Yerevan and the rich farmlands and caravan routes of the Arax valley. It was rebuilt again in 2025 after it became ruins again in the 20th century, and serves as a pedestrian bridge.

5. Churches

In 1828 there were seven Armenian Apostolic churches in Yerevan with a like number of clergy, serving an Armenian population of perhaps 4000. Four of those churches, two of them tiny, survived the Soviet period. Before the grand S. Grigor Lusavorich Cathedral was built in 2001 two blocks E of Republic Square, only one-tenth of one percent of Yerevan's population could attend services at any given time.

The oldest surviving church in Yerevan, the 13c Katoghike, stands at the corner of Abovyan Street and Sayat Nova Blvd. It is today in an open square in front of new larger churches and an office building of the Armenian church, but this was not always the case. In the Soviet period the small church was abutted by a substantial but undistinguished basilica rebuilt in 1693/4, was in 1936 slated for destruction in the name of urban renewal. Archaeologists won a modest concession from Stalin's architects, allowing them to oversee the dismantling and record the inscriptions and architectural fragments incorporated in the rubble walls. Lo and behold, as the walls came down it became clear that the central apse, the sanctuary, was in fact an almost intact small Astvatsatsin church with inscriptions from the 13c. Public and scientific outcry won the newly discovered church a reprieve, though the Soviet government closed it to services and surrounded it with buildings which hid it from street view. Since independence it has resumed its religious function, and more recently the buildings blocking it from the street view were torn down, creating an open square, while church offices were built behind it. By the church is a small collection of khachkars and other sculpted fragments from the core of the destroyed basilica.

The 17c Poghos-Petros (Peter and Paul) church was not so fortunate, destroyed to build the Moscow Cinema. Likewise the S. Grigor Lusavorich church, begun in 1869 but not finished till 1900, gave way to the widening of Amiryan Blvd, and sits underneath the Yeghishe Charents School.

The Zoravar Church survives concealed behind apartment fronts in the block bounded by Saryan, Pushkin, Ghazar Parpetsi, and Tumanyan streets, a hodgepodge of architecture dating from 1693 (funded by the wealthy Hoja Panos) and rebuilt at various times, including by local dignitary Gabriel Yuzbashi in the late 18c and French-Armenian benefactor Sargis Petrossian in the 1990s. According to ecclesiastical history, it sits near the site of the tomb/shrine of S. Ananias the Apostle.

In 1684, at the request of King Louis XIV to the Shah of Persia, French Jesuits set up a mission in Yerevan, goal of which was to persuade the Catholicos in Ejmiatsin to bring himself and his church into the Catholic fold. Effectiveness of Jesuit diplomacy was reduced by their habit of dying after a few months, but the second of them, Father Roux, became friendly enough with the Catholicos that when he died in 1686 he was buried by the Catholicos in the "magnificent monastery of Yerevan" next to the Armenian bishops and archbishops. When the newly enthroned Shah Hussein banned wine throughout his dominions in 1694, the missionaries mourned the destruction of Yerevan's vintage, "the best wine in the Persian Empire." Local authorities respected the extraterritoriality of the Jesuits, putting seals on the door of the Mission wine cellar in such a way that the door could still be opened. Nothing remains of the Jesuit mission, nor of the "magnificent monastery of Yerevan" that housed their mortal remains. Yerevan now has a small scholarly outpost of their spiritual descendants, the Mekhitarist fathers, whose headquarters at the San Lazarro island monastery in Venice is full of great art treasures.

In September 2001, the massive Surb Grigor Lusavorich Cathedral (St Gregory the Illuminator) was completed to mark the 1700th anniversary of Christianity in Armenia. The main cathedral seats the symbolic number of 1,700 worshippers, and there are two large chapels near the entrance which are primarily for weddings. The holy remains of St. Gregory were brought from Italy in time for the opening, and Pope John Paul II came to pay an official visit shortly after the consecration.

6. Mosques

At the time of the Russian conquest there were eight mosques in Yerevan. On the capture of the city in 1827, the grateful and prudent inhabitants (both Muslim and Christian) bestowed the fortress mosque on the conquerors to serve as a Russian Orthodox church until a more suitable structure could be built for the purpose a few years later. The largest mosque of Yerevan and only one still preserved, is popularly called the Blue Mosque (the proper name is Gyoy or Gök-Jami -- gök means "sky-blue" in Turkish) was built in AH 1179 or AD 1765/6 by the command of local ruler Hussein Ali-Khan to be the main Friday mosque. The mosque portal and minaret were decorated with fine tile work. The central court had a fountain, with cells and other auxiliary building around it, and stately elm trees. There was an adjoining hamam and school. In Soviet times, the mosque housed the Museum of the City of Yerevan, which is now within the city hall building. In the mid-1990s, the powerful Iranian quasi-statal foundation for religious propagation agreed to fund a total restoration of the mosque with shiny new brick and tile. This restoration, structurally necessary but aesthetically ambiguous, was largely finished in 1999, and it is now a functioning mosque once again. There is supposed to have been a working mosque somewhere in Yerevan during Soviet times; made superfluous by the 1988-91 population transfers, it burned down.

In Kond, the Tepebaşı Mosque ⟪40.18075, 44.501754⟫ still stands on Rustaveli Street, though it has been organically incorporated into a number of the neighborhood's typical shack-like homes. A beautifully tiled piece of another mosque, the vast majority of which is no longer to be found, remains standing near the Glendale Hills development.

7. The Museums

There are dozens of museums in Yerevan, mostly house-museums to writers, painters, and musicians, with minimal entry fees.

The best museum in Yerevan is small and idiosyncratic, the would-be final home of famed Soviet filmmaker Sergei Parajanov (1924-1990). Though an ethnic Armenian (Parajanian), he was born in Tbilisi and spent most of his professional career in Kiev or Tbilisi. He won international fame with "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors" and "The Color of Pomegranates," but his career was crippled by imprisonment (for homosexual liaisons) and denial of resources. Under perestroika, Yerevan claimed him as its own, and built him a lovely house ⟪40.17868, 44.50004⟫ overlooking the Hrazdan gorge in an area of ersatz "ethnographic" buildings on the site of the former Dzoragyugh village. Alas, Parajanov died before the house was finished, but it became a lovely museum/memorial that also hosts dinners and receptions to raise funds. Parajanov's visual imagination and subversive humor are represented in a series of compositions from broken glass and found objects. His figurines from prison-issue toilet brushes are proof that a totalitarian, materialist bureaucracy need not prevail. Look for "The Childhood of Genghis Khan" and Fellini's letter thanking him for the pair of socks.

The Matenadaran (manuscript library) is another world-class museum in Yerevan, not for its exhibitions per se, but rather for its status as the eternal (one hopes) repository for Armenia's medieval written culture. A vast gray basalt mass at the top of Mashtots Blvd. (built 1945-57, architect M. Grigorian), the Matenadaran is guarded by the statue of primordial alphabet-giver S. Mashtots (ca. 400) and those of the other main figures of Armenian literature: Movses Khorenatsi (5th -- or maybe 8th -- century "father of Armenian history"); Toros Roslin (13c manuscript illuminator in Hromkla/Rum Qalat near Edessa); Grigor Tatevatsi (theologian of Tatev Monastery, died 1409); Anania Shirakatsi (7c mathematician, studied in Trebizond, fixed the Armenian calendar); Mkhitar Gosh (died 1213, cleric and law codifier); and Frik (ca. 1230-1310, poet). There are khachkars and other ancient carved stones in the side porticos. The entry hall has a mosaic of the Battle of Avarayr, and the central stair frescos of Armenian history, all by H. Khachatrian.

Guides are available. Beside the exhibit hall there are conservation rooms and shelf on shelf of storage (closed except to specialists with advance permission) for the 17000 manuscripts in a dozen languages. Cut deep in the hillside behind, and shielded by double steel blast doors, is a splendid marble tomb designed to preserve the collection against nuclear holocaust. A major renovation and expansion took place in the early 21c.

The State History Museum in Republic Square (formerly Lenin Square) is notable for the statue of Lenin squirreled away in a back courtyard ready for any change in the political winds, though the most famous artifact inside is the oldest leather shoe in the world. The important archaeological collection from Stone Age through Medieval periods should not be missed. Note a Latin inscription from Ejmiatsin attesting to the presence of a Roman garrison. There are some interesting models of early modern Yerevan and other historical exhibits of interest to those comfortable in Armenian or Russian.

The floors above contain the National Picture Gallery. Start by taking the elevator to the top, then descend through the huge collection of Russian, Armenian, and European works, some of the latter copies or else spoils of WWII divided among the various Soviet republics.

Accessible from the street running behind the State History Museum is the Middle Eastern Museum and the Museum of Literature. The former houses Marcos Grigorian's personal collection of interesting objects from Persia, including antique door knockers, ceramics, faucets, and other objects, as well as his own artistic works.

The Museum of the City of Yerevan has a small archaeological and ethnographic collection. It is located in city hall on the corner of Zakyan and Grigor Lusavorich.

The Genocide Memorial and Museum at Tsitsernakaberd ("Fortress of Swallows") sits on the site of a Iron Age fortress, all above-ground trace of which seems to have disappeared. The Museum's testimony to the 1915 destruction of the Armenian communities of Eastern Anatolia is moving, and the monument itself is austere but powerful. The riven spire symbolizes rebirth, as well as the sundering of the Eastern and Western branches of the Armenian people. The view over the Ararat valley is striking. Turning away from the wall of recent martyrs and gazing south, a Western Christian might muse on the 10,000 Martyrs of Mt. Ararat, who are in the Catholic Roman Martyrology for March 18 and June 22. According to a legend that somehow made its way westward to become popular in 14-15c art, 9000 Roman soldiers sent out to the Euphrates frontier with a certain Acacius were led by angelic voices to convert to Christianity. The enraged Roman emperors sent troops against them, another 1000 of whom converted when the stones they threw rebounded vainly from the pious converts. Finally, the 10,000 were subdued and crucified atop Mt. Ararat. A painting of this scene by the late 15c Venetian artist Carpaccio shows the persecutors in Turkish garb. Though the legend is too hopelessly garbled to link to any known historical event, and the 10,000 are not part of the Armenian or Orthodox canons, it is tempting to view the cult as the echo of one of several early Armenian cries to the West for help, help that did not come. Purported relics of these martyrs can still be found in various churches of France, Italy and Spain.

For additional information and photos of Armenia's museums visit: Museums of Armenia

8. Soviet Armenian Architecture

While overall the term Soviet architecture has a negative connotation in the west, much of the Soviet architecture in Yerevan is appealing, and some of it is either quite impressive, quite beautiful, or both. With a downtown filled with 5 story pink stone facade buildings and many parks, Yerevan managed to emerge as a unique and endearing city. No visitor to Yerevan can miss the epic stairwell known as Cascade (or Kaskad), with countless built-in fountains. This focal point of the city also today has a lot of very fancy art, much of it monumental, from famous artists around the world. The art is found both inside and outside of the stairs.

The Opera house is another important piece of architecture, with two halls and an oval shape, it sits at one of the important crossroads of the city. The iconic Sasuntsi David Statue and Yerevan Train Station combination are seen by fewer visitors now that train is no longer a primary mode of travel, but they remain as a symbol of the city. The entire Republic Square architectural complex could be considered one of the finest combinations of grand Soviet squares with Armenian local stone facades and decorative stonecarving. The Matenadaran does an excellent job of bringing traditional Armenian architectural elements into the modern world. At a prominent location near the genocide monument sits the impressive Hamalir sports and concert venue (now named after Karen Demirchyan), reminiscent of a darker Sydney Opera house. Gone today was the former Youth Palace of Yerevan, a fun tower at the top of Abovyan that was endearingly known as Kukuru (corn cob) due to the obvious resemblance. Not quite in Yerevan's boundaries but greeting most visitors is the original Zvartnots Airport Terminal. The original Soviet terminal which is today not in use resembles a UFO and the fate of the building is under discussion.

A shortlist of less important buildings worth a look for architecture buffs are Kino Rossia, Kamerayin Tadron, the Chess House, the National Assembly, Erebuni Museum, Hrazdan Stadium, Yeritasardakan metro station and the sunken entrance area of Republic Square metro station.

9. Suburbs: Avan, Kanaker, Arinj

The village of Avan, lying in the angle between the Sevan and Garni roads, has been swallowed up by Yerevan. Heading N past the Yerevan Zoo (on the right, larger than it looks) and just before the Yerevan Botanic Garden (on the left, spacious and nice for walks, but much of it unkempt), take the right off-ramp for Garni, but then go straight through the intersection and turn left at the stop sign. Turn immediately right, and head about 1 km up the main road of Avan. Where the main road turns right at a modern monument and cemetery, continue straight past the intersection a few meters, then take the first left down a narrow lane. The church is about 300m along, on the left. Like many other early churches, this one is known locally as the Tsiranavor ("apricot-colored"). Avan Cathedral ruins =35= ⟪40.2151, 44.5719⟫ is the earliest surviving church inside the Yerevan city limits, dating to the late 6c. At a time when Armenia enjoyed competing pro-Persian and pro-Byzantine katholikoi, the Avan church was built by the pro-Byzantine Catholicos Hovhannes Bagavanetsi (traditional dates 591-603) as his headquarters, while his pro-Persian rival sat in Dvin. Multi-apsed, built on a two-step podium, the church preserves a low arched doorway but is roofless. Historian of Armenian architecture T. Toramanyan believes the church had five peaks - one in the center and the other four in the corners, over the round side-chapels. A surviving inscription preserves the name Yohan in a plausibly early style, but with no title to confirm that this commemorates the founder. The church is built on the site of previous buildings. Some restoration has been done to it in 1940-1941 and in 1956-1966, 1968. There are ruins of monastic buildings N, perhaps the modest seat of one of the catholicosates.

On a slope S of the early village, now on the edge of town, are two chapels, of Surb Hovhannes and Surb Astvatsatsin, with interesting carvings. Restored several times over the ages, they are believed to originate from the 5-6c. They underwent major reconstruction in the 13c, but have spent three centuries in ruins since the 1679 earthquake. The Avan cemetery on the west edge of the town has khachkars of the 13-18c and, across the road, the uninscribed stepped plinth and broken pillar of a 5-6c grave monument.

Kanaker was another important self-standing village in medieval times, now absorbed into modern Yerevan. An important khachkar of 1265 stands with pointed roof near the Sevan road, erected by Petevan and his wife Avag-tikin for the remembrance of their souls. The church of Surb Hakob was dedicated to Hakob of Mtsbina (aka James of Nisibis), an early 4c Syrian bishop who was one of the founders of Armenian Christianity. In Armenian tradition (though not Syriac), Surb Hakob attempted along with his followers to climb the mountain of Noah's Ark (which back then was located in Kurdistan south of Lake Van, rather than its currently popular location, Armenian "Masis" or Turkish "Agri Dag" just across the border from Armenia). Led by a vision, he found a piece of the Ark, which he brought down in triumph. He was famous also for the springs of water that burst forth where he laid his head, and also for leading the defense of Nisibis against the Persians in AD 338. Near Surb Hakob is a large basilica dedicated to the Mother of God. Both churches have elaborate carved entrances. Ruined in the 1679 earthquake, both were rebuilt soon after, Surb Hakob by a wealthy businessman based in Tbilisi, Surb Astvatsatsin by local efforts. Surb Hakob was the seat of the bishop, with a diocesan school founded in 1868. Surb Astvatsatsin was a monastic church, originally walled and with cells. Used as a warehouse in Soviet times, Surb Hakob resumed its churchly function in 1990. In the gorge below Kanaker may still remain traces of a ruined "Tivtivi Vank" and of a stone bridge.

Kanaker is famous also as the home of Khachatur Abovyan, the school-inspector/novelist who elevated the modern dialect of Yerevan to its current literary eminence. Abovian was a nephew of the hereditary chief of Kanaker village, a descendant, in turn, of the Beglaryan clan of meliks of Gyulistan. Abovyan contributed to his fame by accompanying Professor Friedrich Parrot of Dorpat University on the first modern ascent of Mt. Ararat (the local one), in September 1829. Abovyan disappeared mysteriously in April 1848, leaving a wife and two young children. The favorite theory, albeit with no firm evidence behind it, is that he was kidnapped by the Czar's agents to rid the Empire of a potentially dangerous Armenian nationalist in the year of the great European revolutions. The Abovyan house-museum is at Kanaker 2nd street, house 4.

Arinj is a pretty suburb on the right just as you leave Yerevan on the Sevan highway. A road turns right from the main Sevan road 2.8km past the bridge/turnoff to Garni. Arinj is home to Levon's Divine Underground ⟪40.2304, 44.5705⟫, a fantastic collection of rooms and halls carved over 25 years by local villager Levon into the solid rock under his home for 25 years. Extending to a depth of more than 20 meters from the surface, these passages are one of the most unique finds in the Yerevan area. To reach the house (anyone will direct you if you just say Levoni Tun), continue into the village about 1km from the Sevan road. You will see a small post office on your left; turn immediately right into a dead-end alley & park at the end. A small footpath continues in the same direction as the alley and meets up with a dirt road; turn left and proceed to the fourth house on the right (it has carvings in the shape of a flower bell along the roof). Knock at any reasonable hour for entry. Donations are expected.

Other Sites

See also

- Clickable Map of Attractions in Yerevan

- old Soviet Guide to Yerevan Online.

| Rediscovering Armenia Guidebook |

|---|

| Intro

Armenia - Yerevan, Aragatsotn, Ararat, Armavir, Gegharkunik, Kotayk, Lori, Shirak, Syunik, Tavush, Vayots Dzor Artsakh (Karabakh) - (Stepanakert, Askeran, Hadrut, Martakert, Martuni, Shushi, Shahumyan, Kashatagh) Worldwide - Nakhichevan, Western Armenia, Cilicia, Georgia, Jerusalem, Maps, Index |